Tariff war, Bipolar World, Recession, Weekly post (31th march - 4th April)

Geos, Tariffs, Politics, Volatility, Underpriced left-tail

In this post, I will explain the relationship between the EU and the US in the context of the tariff war, and what risks the transforming world order is facing. From this, you will also understand the direct and indirect impacts all of this has on the markets.

It is important to grasp the underlying mechanisms, because the market reacts to them. Take the time to go through it. Unfortunately, many people do not understand these things I’m writing about. They don’t talk about them

Before we look at how the market is pricing itself for the week, there are two important things to mention.

The first is the worldwide geopolitical realignment. This is very significant, because the economic framework we’ve known until now is changing fundamentally, and in this context, all sorts of market trends make sense. The second is the impact of the JPM collar.

Geopolitics again...

I previously described the scenario intended to lay the groundwork for the modern “Holy Alliance,” so that peace may be achieved between the U.S. and Russia. Its foundation is ideological.

I also mentioned that this realignment has ideological roots. Liberalism in the West has degenerated into a kind of self-serving hedonism, which, lacking a guiding ideology, inevitably leads to a collapse of the system over time. On the other hand, left-liberal political forces have monopolized the concept of democracy, and people have forgotten that democracy can exist within a right-wing conservative system as well. In fact, in history, the only functioning democracy was based on strongly ideological and conservative foundations.

The core of any political ideology is what it believes about human nature. This is the basis on which we distinguish the left from the right. On the left, the individual is at the center, and everything else—nation, religion, institutions, etc.—exists to serve the individual. On the right, the individual is also central, but here the individual submits to those preceding and outliving them (nation, religion, ethics, etc.).

The far-right extreme is nationalism, and the far-left extreme is communism. Since they’re extremes, both create total systems, but their ideological core on the wings is the same, so when the conflict between political ideologies becomes sharper, the right and the left don’t cooperate with each other; rather, they gravitate toward the far right or far left, forming alliances there.

That’s why we see the shift among the Republican U.S., Russia, and right-wing European states toward the Arabs and other nationalist states, and among the Democratic U.S. and globalist European countries toward communist China and its allies.

This transformation isn’t yet obvious, but it’s visible, and it’s crucial to understand it in order to make sense of current events and future movements.

Re-bipolarization, economics re-structurization

Trump’s tariffs are intended to force the EU to the negotiating table, compelling it to accept the U.S.–Russia–Middle East peace proposal. The globalist elite rejects this, since it would lead, among other things, to bleeding out the global capitalist systems, meaning they need to look for new allies and sources.

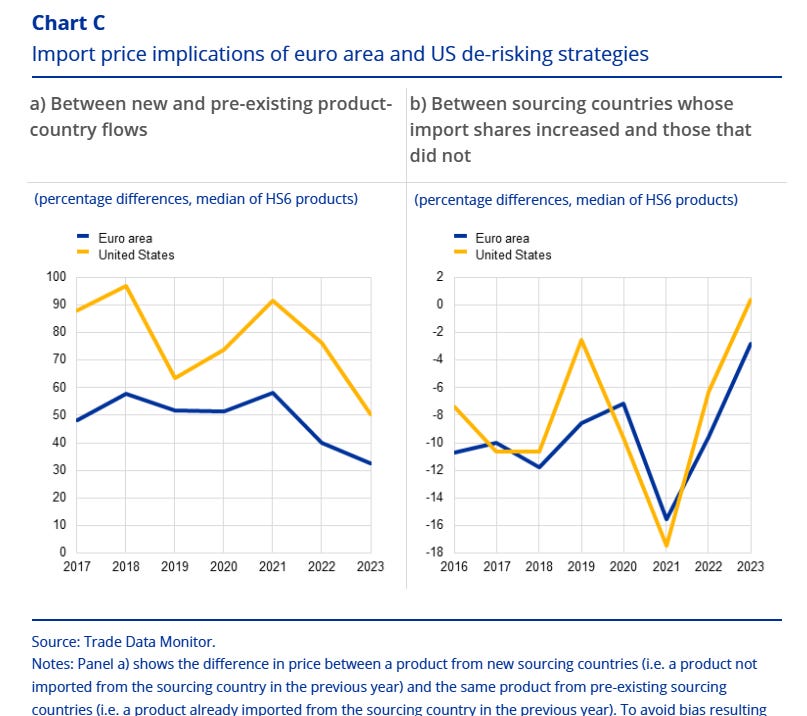

In the charts below, you can see that after the first Trump administration (and the tariff war), a diversification trend began, in which both the EU and the U.S. started to increase the number of supplier countries for strategic products.

The EU’s diversification aimed to reduce dependence on Russia, while imports from China grew. The U.S., on the other hand, aimed primarily at independence from China but also from Russia. However, this comes with increased costs.

In the first months of 2025, the Trump administration enacted several significant tariffs that directly hit European exports:

On March 12, 2025, tariffs of 25% on imported steel and 25% on imported aluminum took effect, applying globally with no country exemptions. The official justification was national security: the U.S. argued that reliance on foreign metals threatened its industrial base, a claim made under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act. European officials criticized this rationale, noting it “disregard[s] the national security imperatives of the United States – and indeed international security” when used as a pretext for protectionism. The EU had actually suspended its prior counter-tariffs on U.S. steel/aluminum during negotiations in 2023, but reactivated plans to retaliate once these new 2025 metals tariffs hit.

On March 26, 2025, President Trump announced a sweeping 25% tariff on all imported automobiles (passenger cars and SUVs) and automotive parts. This import tax on cars, scheduled to begin April 3, 2025, is expected to affect major European automakers (Germany, France, Italy, etc.) which count the U.S. as a key market. The White House estimated the auto tariff could raise about $100 billion annually in revenue. The official reasoning given was economic: to foster U.S. domestic manufacturing and reduce reliance on foreign auto imports. By making imported cars 25% more expensive, the administration aims to push production and supply chains back to American soil (though industry experts warn it will also raise prices for consumers and disrupt supply lines for U.S.-based carmakers).

In a more unconventional step, President Trump ordered a 25% tariff on any country that imports oil or gas from Venezuela in early 2025. This measure, leveraging the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), was ostensibly aimed at pressuring Nicolás Maduro’s regime by penalizing its foreign customers. In practice, it swept up some EU countries (notably Spain and the Netherlands) which historically process Venezuelan crude. Those countries suddenly found all their exports to the U.S. taxed an extra 25% as long as they continued buying Venezuelan energy.

By late March, new tariffs on lumber, microchips, pharma, and copper were planned for later in April, as part of a rolling pressure campaign, though specific rates were not yet implemented. These were justified as efforts to protect American industries deemed critical or to retaliate for what the U.S. views as unfair advantages enjoyed by foreign producers (for instance, the administration hinted at curbing semiconductor imports to press EU and Asian allies to align on tech policies).

April tariffs: the goal is a ceasefire and to defeat stagflation

The administration signaled it would impose a flat, double-digit (20–25%) tariff on all imports from the European Union, aiming for a rate roughly matching the tariffs and barriers the EU applies to U.S. exports. This unprecedented move—treating the entire EU as a single target in a trade war—was justified by the White House as enforcing “fair reciprocity,” arguing that Europe’s own import tariffs (such as the EU’s standard 10% tariff on cars, agricultural duties, and various non-tariff barriers like regulations) have disadvantaged U.S. exporters for years.

As noted, the 25% auto tariff was announced in late March and set to take effect on April 3. By April, the impact on European carmakers was expected to be significant, with essentially all passenger vehicle exports to the U.S. facing a steep levy. Europe’s auto industry is a major exporter (the EU shipped about €37 billion in cars to the U.S. in 2022), so this tariff directly hits a substantial flow of trade.

Following steel, aluminum, and autos, the Trump trade team indicated that new tariffs on lumber, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and possibly chemicals would be rolled out in phases throughout April. For instance, duties on imported microchips and drug products were on the agenda (impacting European tech and pharma firms). These measures were part of Trump’s strategy of incremental escalation—using the threat of further pain to extract concessions in negotiations. By mid- to late April, however, the expectation in Europe was that no major industry would be spared if talks failed; the U.S. was prepared to tax a broad array of EU goods, effectively weaponizing America’s entire import market as leverage.

These tariffs come at a time when the European economy is already grappling with post-pandemic recovery and external shocks (like high energy prices stemming from the Ukraine conflict). Additional tariffs act like a tax on trade, potentially raising costs and prices (inflationary) while dampening demand (recessionary). The European Commission has voiced concerns that tit-for-tat tariff wars could “reignite global inflation” and undercut growth. The EU must protect its economic interests and respond to U.S. trade aggression, but without hurting itself further.

The Trump administration has justified its EU-directed tariffs as a necessary correction to perceived inequities (making the EU pay a price for its trade surplus and higher tariffs), a means to safeguard key U.S. industries and interests, and a leverage tool to negotiate better terms.

But the key is that these tariffs are tools to force the EU to the negotiating table, compelling it to accept the upcoming “Holy Alliance 2.0” peace proposal. As I wrote, Trump needs to resolve this and eliminate Western stagflation by Easter. According to the original plans, a ceasefire should be in place by Q3.

What can the EU do?

In late 2023, the EU passed the Anti-Coercion Instrument, a new legal tool to respond to economic intimidation by non-EU countries. This was designed precisely for situations where a partner uses trade measures to coerce the EU or its members (the law was partly inspired by incidents such as China’s trade blockade of Lithuania). The ACI allows the EU to swiftly implement retaliatory measures beyond tariffs—including restrictions on services, investments, or procurement—if it determines that a foreign country is trying to coerce the EU. Trump’s blanket tariffs and explicit bargaining approach (“do X or face tariffs”) could well be deemed economic coercion under the ACI’s definition. For example, under the ACI, the EU could ban U.S. companies from participating in certain EU public tenders or restrict exports of critical EU goods to the U.S., as a targeted response.

The EU can coordinate its response with other nations also targeted by U.S. tariffs. In 2025, the Trump tariffs are hitting allies like China, Canada, Mexico, Japan, BRICS, and others simultaneously. For instance, the EU, Canada, and Mexico could jointly refuse to negotiate under tariff blackmail and perhaps collectively threaten action through forums like the G7 or G20.

The EU can challenge the U.S. tariffs through the World Trade Organization’s dispute mechanism. In fact, after the 2018 steel tariffs, the EU (and others) brought cases against the U.S. at the WTO. A formal legal challenge claims that the U.S. measures violate WTO rules (for example, the most-favored-nation principle and agreed tariff bindings). While the WTO process is slow and currently hampered (the Appellate Body is not fully functional due to U.S. blockages), pursuing a case still has value. It signals the EU’s principled stance and might eventually authorize the EU to impose WTO-sanctioned counter-tariffs if it wins (essentially legal retaliation).

Also, the European Central Bank can play a crucial role in buffering the EU economy against trade-war shocks. If U.S. tariffs begin to bite, the ECB could loosen monetary policy—for instance, by delaying planned interest rate hikes or even cutting rates/stimulus if growth falters. By keeping credit cheap, the ECB would support European businesses through a rough patch and help counteract any rise in borrowing costs caused by market jitters. An ancillary effect of easier ECB policy is a weaker euro, which helps EU exporters compete internationally (partly offsetting U.S. tariffs, as a cheaper euro makes European goods less expensive in dollar terms). Indeed, in response to the tariffs and the “money goes home” capital shift, the euro has depreciated somewhat—privately welcomed by EU officials as it boosts export competitiveness. They will let the exchange rate adjust naturally as a shock absorber. The ECB will also be ready to provide liquidity to financial markets if necessary (through asset purchases or swap lines) to prevent a credit crunch in Europe if U.S. actions cause severe market dislocation. Essentially, monetary policy is a tool to stabilize confidence: as the U.S. raises import barriers, the ECB can reassure firms that financing will remain available and that policymakers are supporting demand. This mitigates recession risk. (One must note, however, that the ECB’s primary mandate is controlling inflation. If tariffs drive inflation up via higher import prices, the ECB faces a balancing act. Yet given the priority of maintaining growth and financial stability, it will likely err on the side of accommodation, as President Lagarde has indicated openness to looking through one-off price impacts in favor of the broader outlook.)

On the fiscal side, the EU (and member state governments) can deploy spending and subsidies to blunt the tariffs’ impact. The European Commission could temporarily relax its strict budget rules, allowing member countries to run slightly higher deficits to fund relief measures.

In an extreme scenario where capital flight from the EU becomes destabilizing (for instance, if U.S. companies begin divesting en masse or if the dollar soars in value at the euro’s expense), the EU could consider measures to manage these flows. Full capital controls are unlikely in a free-market EU, but heightened investment screening might prevent opportunistic takeovers of strategic European firms if their valuations drop. EU regulators could also coordinate to discourage hasty withdrawals—for example, by diplomatically urging U.S. multinational companies not to cut and run from European operations, or by highlighting the long-term costs of leaving. The EU could seek support from other global investors (such as sovereign wealth funds from friendly countries) to step in and invest in Europe, offsetting any U.S. pullout. The key is to ensure that if “some money goes home” to America, other money comes into Europe from elsewhere. By maintaining an attractive investment climate—i.e., not retaliating in ways that scare off all foreign investors—the EU can mitigate the financial impact.

On the defensive side, the EU can adjust its import sources. Higher U.S. prices (whether due to tariffs or any EU response) mean Europe can replace some U.S. imports with domestic or alternative foreign suppliers. The EU had already implemented steel import safeguards in response to Trump’s steel tariffs—basically limiting imports from elsewhere so that steel diverted from the U.S. would not flood Europe. It could tighten these quotas further to protect EU steelmakers who are now hurt on the other side by U.S. tariffs. For agricultural commodities, if the EU imposes countermeasures not as tariffs but rather as quotas or restrictions, it can manage supply. Additionally, reducing dependence on U.S. high-tech inputs (such as certain semiconductors or software) is already a strategic goal for Europe; the trade war merely reinforces the drive for tech sovereignty (e.g., investing in European chip fabs so that U.S. export restrictions or tariffs on chips are less harmful).

On the offensive side, the EU could speed up negotiations on trade deals with willing partners. For example, finalizing pending EU trade agreements with countries like Australia, India, or the Mercosur bloc (Brazil/Argentina, etc.) could open new markets for European goods. If American protectionism closes one door, opening others is crucial.

And the most important thing: China and the EU could directly strike at U.S. economic interests. U.S. Treasuries are viewed as the benchmark for global financial stability. If the EU sold off a significant portion of its holdings, it could depress bond prices and push up interest rates. This sudden shift could unsettle global financial markets, leading to higher volatility and elevated borrowing costs—not only in the U.S. but worldwide.

That’s why we saw a small increase in CDS prices when the PCE figures came out:

The timing is very telling. Look at how much it has risen in relative terms over the last few weeks.

Such an aggressive move would definitely hit the EU as well, since it would destabilize global markets, and the EU can’t reposition itself that quickly (and I doubt it’s intended to). However, it is temporarily financing military resources and commodity stockpiles for its reserves.

In a bipolar, fragmented world, commodity prices become far more sensitive to various external shocks than in a globally cooperative, integrated world. Furthermore, as countries migrate from one bloc to another, exchange rate dynamics change. Restricting free trade leads to a smaller economic surplus.

I recommend reading the IMF’s 2023 paper on re-polarization.

Sell-off, bottom

What we’re seeing now is that despite Friday’s events, the market seems complacent. It’s not taking the trade war seriously, which is quietly and gradually unfolding under the hood. (I know many of you think this is just a theory, but once these events pass, you’ll see in hindsight what really happened. Maybe Trump will explain it one day—though he’s risking an American civil war with every move.)

This could lead to a black swan scenario around tariffs. On the other hand, there’s the U.S.–Iran standoff, for which Trump needs Putin to help find a resolution. additional vol events ahead are ISM and NFP.

And as I mentioned, a fragmented world economy fundamentally raises the average annual volatility. Market is not prepared. They don’t see it.

As I posted earlier, the biggest interest is in tech. That’s were the selling is going on. As much as I’m allowed to say, the U.S. wants to buy out China’s stake in major tech interests like NVDA—which faces significant China-related issues—and AAPL, where manufacturing is in China and AI progress is restricted by slower iPhone demand. Arabian funds don’t give their money to China. MSFT is a major target to long later around Q3, partly due to its Dubai division, which they can then control.

Insiders expect bottoming after Easter, into Q3. I would say, around last year April levels.

JPM Collar expiry

Before we move on to the weekly skew, I need to mention the JPM Collar expiration on Monday.

In last week’s weekly post, I already explained how the collar works in detail. It’s very important to understand this, because there’s a lot of misinformation about it on social media.

The collar primarily affects the vega profile in the weeks leading up to expiration. Its impact is especially significant near the short call strike and below the long put strike at expiration, due to gamma.

As I wrote, they let the collar expire—they don’t close it. Meanwhile, around 2 PM, they open a new collar, which they delta-neutralize with a 0DTE call to remove the extra synthetic short exposure the double collar would otherwise create during the final two hours.

If the spot is above the long put strike (5565), there can be only a mild supportive effect. The OTM expiring put spread provides minor support, which the new collar largely absorbs. However, if the put spread expires ITM, then short vanna, long charm, and short speed create a suppressive environment toward the lower leg (4700), roughly towards 5114.24

The collar’s psychological impact is bigger than its actual influence on flows. And the funds know this, which is why they play with it.

I caution everyone against overemphasizing dealer flow or any single effect. Dealer flow mostly has microstructural impacts. The macro picture is told by the market’s overall story, which places daily positioning changes and volatility cycles into context.

Let’s look at the skew…

WEEKLY OUTLOOK/CONTEXT

Here is the skew as it looks like now, into Q3